|

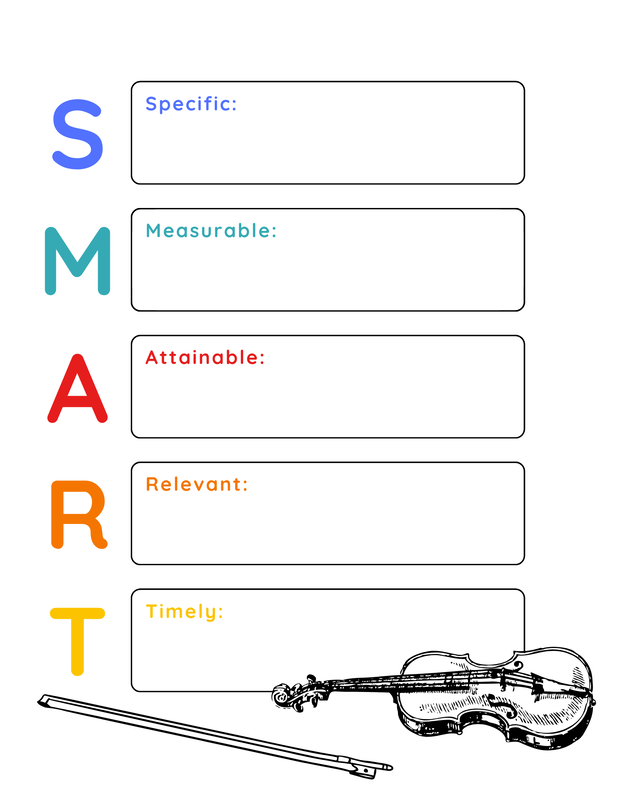

The capitalized term SMART Goals is an acronym and refers to an evidenced-based formula for achieving a goal. The term "evidence-based" means using the best available research to inform decision-making, interventions, or strategies based on scientific research, and I propose we bring evidence-based practices into our work as musicians. A "smart goal" for any violinist would be "I want to practice my vibrato more." And who can argue with that? It is not a bad start, but it is akin to saying come to my house for dinner & leaves us with several voids: Where do I live? How do you get there? What date works best? When should you arrive? Are there any cats? Are you allergic to cats? Do you have any food preferences? Etcetera, etcera. Saying, "Come to my house for dinner," is not specific enough to create the best outcome, and the same problem happens when we settle with using vague goals for our violin playing. Using the "SMART goal" paradigm, the goal to practice vibrato more would turn into: "At the start of every practice session, Monday-Friday, for the next 3 months, I will set my timer for 8 minutes and work on technical exercises X, Y & Z, being conscious of the excess tension I am holding in my *tongue and eyes and then I will spend 6 minutes playing 1-octave G, D & A major scales in whole notes while I transfer my vibrato technicals into my violin playing." *I know that probably sounds weird, but believe it or not, this body part is usually too activated and tense. Phew! Can we agree that's quite a different goal? Which violinists will make better use of their time and progress faster? What exactly is a SMART goal? The capitalized term SMART Goals is an acronym and refers to an evidenced-based formula for achieving a goal. The term "evidence-based" means using the best available research to inform decision-making, interventions, or strategies based on scientific research and proven outcomes and is the standard approach in the medical field. It can also be seen in education, sports, and policymaking. I propose we bring evidence-based practices into our work as musicians. The SMART acronym stands for:

The gist of the entire SMART goal concept is getting specific. Let's look at each SMART goal template component to understand better how this can benefit a violinist. Specific: Define goals clearly and precisely. Taking our example of "to practice vibrato more," we can add a particular quality to this goal; perhaps we seek to make our vibrato more natural and less tense. Or, perhaps a particular finger, part of the hand, or arm needs to be adjusted in its angle to get a better-sounding vibrato. If you are still trying to figure out what better means for your musical goal, think about techniques because these are the ingredients for making something better. Measurable: Establish criteria for tracking progress. The example provided used time as a measurement: 8 minutes of technicals followed by 6 minutes of applying these into one-octave scales. Additional measurements for musicians include the quantity of repetitions, the number of bars to memorize, or a metronome tempo. Achievable: Set realistic and attainable goals. Yes, it's very exciting to set the goal to learn all of the unaccompanied solo Bach Partitas and Sonatas, but is this achievable for a 17-year-old high school senior to accomplish in 3 months while concurrently auditioning for different colleges? Realistic: Ensure goals align with broader objectives. This ties in with the achievable aspect of SMART goals. Our sample high-school-aged violinist above may be prodigious in their capacity, but this also occurs while completing their high school coursework and in the middle of their basketball season. You get the idea, which is why each part needs to be individualized to the musician and the context of their broader life. Time-bound: Set deadlines for goal completion. For this 17-year-old talented student in the middle of their extra-curricular sports, auditions, and coursework, perhaps they can learn the entire repertoire of unaccompanied Bach. It is just that the timeline needs to be appropriate, and they can focus on one Sonata or Partita every 6 months for the next 3 years. Timelines, when used appropriately, create the structure to soar. Drawbacks of the SMART goals system: It is exciting to use formats like the SMART goals to help us achieve our human potential and use evidence-based research to support us in living our dreams, but they are without limitations. 1- The first drawback is that it may be too cumbersome and time-consuming to apply a SMART goal to every portion of a musician's practice curriculum (scales, rhythm, etudes, repertoire, ensemble pieces & solo preparation). It could easily take an hour to collaborate on creating a SMART goal for each portion of a violin student's curriculum, which is not likely a good use of time. m 2- Next, SMART goals do not permit the exploration element because it is so specific. Playing music should involve playing in the true sense of the word "play." Resources for goal setting: I am no stranger to writing about the importance of setting goals, and I aimed to model & create structures for this for my students when I was actively teaching. I started thinking of goals as being like GPS coordinates for your dreams when I first wrote about this subject in 2018. This led to the creation of goal-setting resources (like the Rainbow Goal Sheets for sale in the store and free samples on the FREEBIES page). My passion for this topic continues because I find it relevant as I progress through different developmental stages as an adult. I also chose the example of vibrato in this post because some students and teachers need help with this element of music-making. If you have yet to see my video on vibrato, check it out here and learn an easier and ergonomic way to do vibrato on the violin. Lastly, please help yourself and download the SMART goal worksheets below to use with your students to help make this concept more tangible and accountable in a lesson structure.

What do you think of SMART goals? Can you see yourself using this? Do you have any criticisms? Please join in the conversation and post some feedback below.

0 Comments

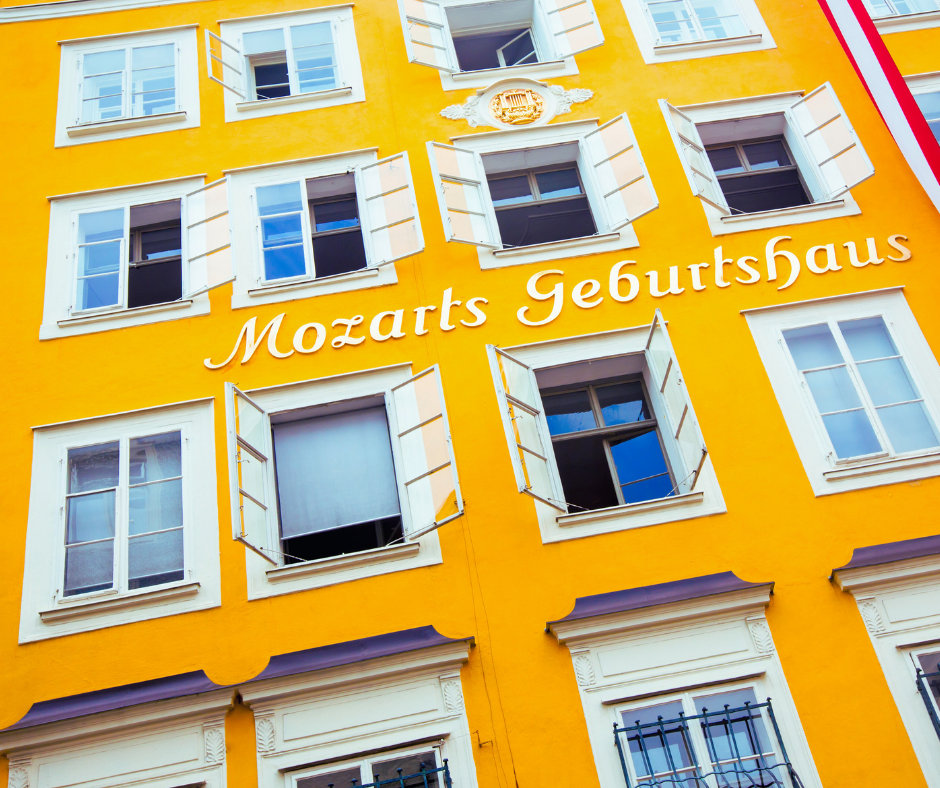

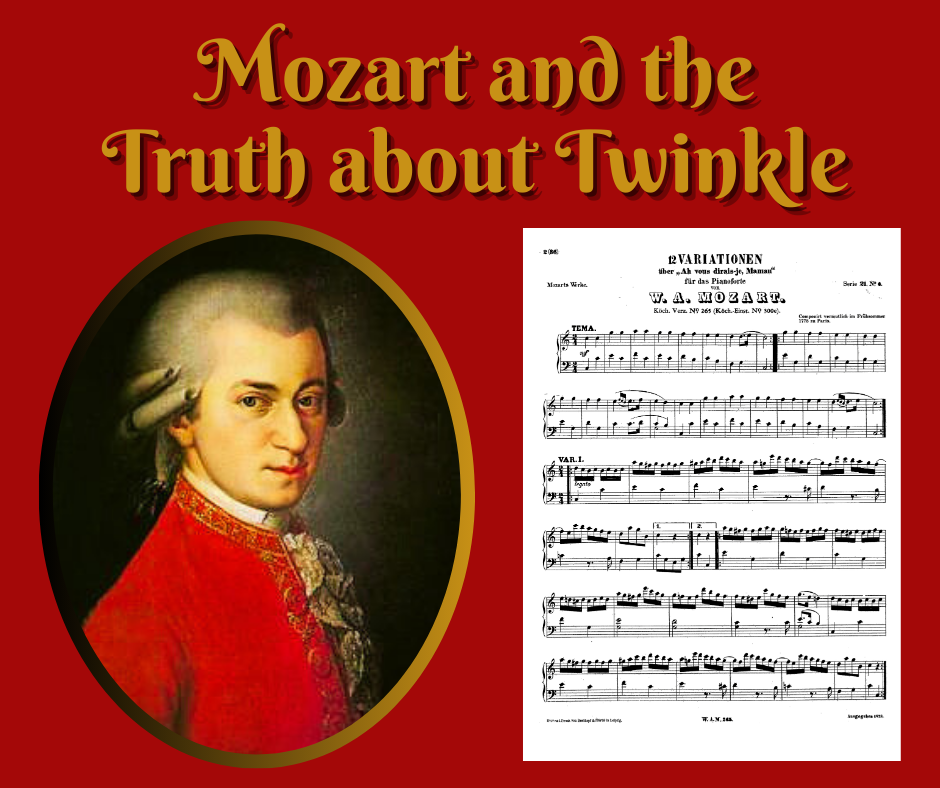

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born on January 27, 1756, and is a legend in the music world! He started composing at age 5 and touring at 8. When he turned 13, he received sensational press reviews stating he was a "miracle in music, one of those freaks that nature causes to be born." In his 35 years, this virtuoso violinist and keyboardist composed 800 pieces (though this number varies by different sources). I was exposed to the Der Spiegel (The Mirror) Duet as a teenager. This sheet music is designed to be played on a tabletop and demonstrates his unrivaled conception of the musical staff by being able to conceive of it simultaneously right-side up and upside-down. You can access a free PDF here. Later, as a teenager, I visited Europe with my mother and indulged in "Mozartkugel" or Mozart balls - a chocolate candy melodically combining pistachio marzipan and hazelnut nougat with a picture of Mozart on the wrapper. In college, I became dismissive of W A. Mozart's music - I thought it sounded too fluffy and predictable. It was not until I read his biography about his upbringing that I understood how difficult his life was and that music was a way to transcend his challenges. When I started teaching, a colleague turned me onto the violin duets his father, Leopold Mozart, composed, and they have been some of my favorites ever since. They are available on Amazon in case you are interested. Modern AI can even help us see what he looked like. A channel on YouTube recently did a facial reconstruction of what Mozart looked like in his day and what he would likely appear as in modern times, along with a concise biography of his life: Mozart: The Funny, Rebellious Prodigy. History Documentary, Including Facial Re-creations. So let's talk about Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star. This simple tune has permeated my musical experience, and I have taught it to students for decades and have a fondness for arranging it (here are all my collections). But I got it wrong - it was not likely composed by W.A. Mozart.

One of my favorite M4YV blog posts ever was by guest author Murray Charters (B. Mus., M.A.) Cellist and Teacher from Kitchener, Ontario, who educated me on the origins of Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star. I had gone decades of my musical life assuming this tune from W.A. Mozart until I read this. Click on the button above to learn more. Who wrote Twinkle?For decades, I thought this clever tune was composed by W. A. Mozart until a colleague enlightened me. Enjoy this delightful re-post by guest author Murray Charters from 2015. By Murray Charters (B. Mus., M.A.) Cellist and Teacher, Kitchener, Ontario Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91) holds great appeal to teachers and students of the Suzuki method. There are pictures of the young boy playing the harpsichord with his older sister, Nannerl, and we know much about the strong guiding hand of his father, Leopold, in his music education. They were already a Suzuki family! Wouldn’t it be nice to connect clever young Mozart with the most famous tune in Suzuki literature? Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91) holds great appeal to teachers and students of the Suzuki method. There are pictures of the young boy playing the harpsichord with his older sister, Nannerl, and we know much about the strong guiding hand of his father, Leopold, in his music education. They were already a Suzuki family! Wouldn’t it be nice to connect clever young Mozart with the most famous tune in Suzuki literature? Nannerl recorded that her brother started composing simple keyboard pieces around age 5, and his first symphony at age 8. By that time he had already travelled to many of the important cities of Europe and actually wrote that first symphony to pass the time while his father recovered from a cold when they were in England. On the way to England they had stopped in Paris where a collection of folk songs had been published just a few years earlier, in 1761. That collection included a very attractive little song, without lyrics, said to have been created in the then popular pastoral style some 20 years earlier by author or authors unknown. This tune proved so appealing that it was published again in Paris in 1774, this time with lyrics of a rather sophisticated nature added. "Ah! vous dirai-je, Maman" is the first line of an anonymous love poem of the time. Of course it’s about love; it’s French isn’t it? “Oh! Shall I tell you, Mother / What is tormenting me?” the poem begins, and goes on to exclaim: “Can anyone live without love?” These lyrics speak of teenage angst rather than nursery rhyme cuteness, but that was soon to change. In 1806 a young English poet, Jane Taylor, published a six-stanza poem called The Star in a book of Rhymes for the Nursery. Whether intended or not, Taylor’s poem fit very nicely onto this French folk song. In fact, others must have thought so too and her words were eventually printed together with that music in an 1838 song book. And thus it was that what we now know as “Twinkle, twinkle, little star” finally made its first appearance on the world’s stage in that form in the second year of the reign of Queen Victoria. So how did we come to associate this well-known English nursery rhyme and French folk song with Mozart, especially in Suzuki circles? Because both he and Dr. Suzuki knew a good melody when they heard it. Mozart wrote a splendid set of keyboard variations on this tune around 1781 or 82. But he called it “Ah! Vous dirai-je, maman” which shows he knew the melody only after its French publication of 1774. He certainly wasn’t the only composer attracted to all the possibilities for variation offered by this simple but elegant tune. Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach, 9th son of J.S., did the same thing around the same time, and there have been other sets written since, but none by composers with names of the musical appeal of Mozart. (I particularly recommend the Variations on a Nursery Tune for piano and orchestra by Ernst von Dohnanyi, perhaps because of its subtitle: For the enjoyment of humorous people and for the annoyance of others.) I’m sure these musicians saw the same things in this melody that we all point out to our eager music students. Its immediately innocent nature using just six notes of the scale, a very simple rhythm pattern, and much repetition belies a more sophisticated emotional tone set by the refusal of the middle section to return to the tonic. Of course this charming melody is also absolutely ideal for creating good posture for little left hands on bowed stringed instruments, and we should all praise Dr. Suzuki for using it so cleverly at the beginning of his method. Just don’t say it was written by Mozart. A very special thanks to Murray's Music for contributing this article to the Music for Young Violinists Project! |

Categories

All

Archives

February 2024

AuthorHi! It's me, Heather. I absolutely love working on the Music for Young Violinists project and all the many facets: blogging, website, music, teaching materials, freebies, videos, newsletter and giveaway contests. The best part is connecting with you so feel free to drop me a line. You can learn more about me on the "ABOUT" page. Thanks! |

||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed